Think of a Goth and you might think of morose devil worshippers dressed in

black. The reality, finds Ruth Dickinson, is often different – a friendly

sub-culture willing to explore their spirituality.

Last week, 25-year-old Kimveer Gill was shot dead by police after going on a

shooting rampage in a college in Montreal. One woman died, and 19 others were

wounded.

Reports towards the end of last week revealed snippets of insight into his

troubled mind, perhaps evidence of what drove him to do what he did.

Gill was a loner who loved massacre video games. He was also a Goth, who spent

many hours posting pictures and messages on various Goth and vampire websites,

including an express desire to die ‘in a hail of gunfire’.

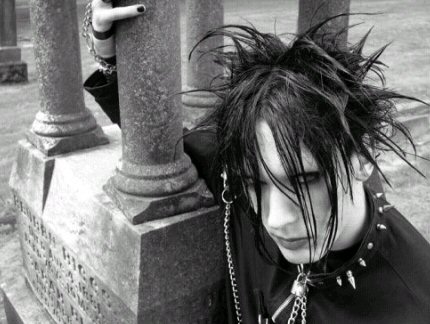

For some people, even the stereotypical image of a Goth – black clothes, white

faces, a copy of Anne Rice’s Vampire Chronicles, and a preoccupation with misery

and death – will be foreign.

Either way, Gill’s story – playing out for real the Gothic fascination for

nihilism – does not help the image of a subculture with most ordinary Christians

would feel they have nothing in common with at all.

These are people who appear to have accepted and alternate identity which is at

best alien and at worst antagonistic to the average Baptist believer.

So meeting a Christian Goth is not a just a fascinating experience, it is an

object lesson in how a preoccupation with the darker side of life does not

necessarily equate to a preoccupation with evil.

For a start, Goths are not all violent gun-toting crazies who are about to go

running into a school and shoot everybody. ‘Most of us are peaceable,’ says

20-year-old Ash Ford from Norfolk.

She has been a Goth for about three years, having met some at college. ‘All my

life I have felt a bit left out. I tried to fit in but somehow it just didn’t

work. When I left school and went to college, there were a group of Goths there

and I started talking to them.

‘It was the first time I’d had a very deep and interesting conversation with

people my own age.

‘I felt like I had more in common with them than with anyone else.’

For the uninitiated, it is worth looking at what a Goth actually is. Definitions

are various – any Goth site on the internet will give you half a dozen variants,

and as the Revd Marcus Ramshaw, assistant chaplain of St Edward King and Martyr

Church in Cambridge, points out, even Goths themselves struggle to define what

one is.

‘Trying to define a “modern-day Goth” is a torturous exercise,’ he writes in an

article Being Christian and being Goth. ‘Most Goths themselves refuse to

acknowledge the label. They continually debate amongst themselves what is

“gothic” and what is not.

‘I think it is principally a state of mind, an attitude towards the world, a way

of viewing those around you,’ he continues. ‘For the modern day Goth this is a

deep identity with the darker dimensions to our existence.’

Certainly, there seems to be a general consensus that being a Goth goes deeper –

and often darker – than what you immediately see. It’s not just about dressing

up, though it was the aesthetic side which first attracted Joe Banks (18). He

acquired a black leather jacket – ‘very retro’ and for a laugh he put on some

makeup. ‘I thought, “This looks good,” so I carried on doing it.’

For Joe, the Goth psychology can be summed up as delving deeper into things,

looking at what is beneath the surface. ‘It’s looking at something which you may

not find beautiful and finding beauty in it.’

‘It’s about looking at the whole of life, looking deeper into it than the rest

of society seems to,’ agrees Ash.

Image is an important expression of that. Black is the default colour of dress,

but there are many variations. Joe lists off styles including ‘cyber Goths’

(‘who are into techno and trance and wear luminous things’) ‘punk Goths’ (‘who

are closer to punks but still Goths’) and elegant gothic aristocrat (very smart,

Romantic, lots of waistcoats, pocket watches).

The aesthetic is an integral part of being a Goth, though interestingly, Joe

chooses to dress more conventionally when he works – currently as part of a

youth scheme at the Diocese of Chichester.

‘I do it because it can be a barrier,’ he explains. ‘If you’re talking to young

people or children, you don’t have much chance to talk about them; they are

asking too many things about you. And it can look a bit scary. Also, it’s a

practical thing – you don’t want to be wearing boots and chokers and high starch

collars when you’re running around playing games.’

So the external image is important, but no more so than being honest and

expressive about what is going on the inside, even if that means being negative.

‘Pain and heartache are taken very seriously’ says Marcus. ‘Many modern day

taboos in contemporary society such as self harm, suicidal thought, depression,

grief, failure and fear will resonate with Goths far more powerfully than most

other modern subcultures would realize.’

Certainly a lot of them are troubled, and given to introspection. ‘You’d never

find that “Miss Popular” at school is now a Goth,’ says Joe. ‘They tend to be

the one’s that didn’t fit in at school, the outcasts. And there is a bit of doom

and gloom. But we’re not all walking depressives – we don’t all want to slit our

wrists all the time. We do smile, we don’t walk around trying to look sombre all

the time.’

For Ash, introspection and self-examination is necessary and even positive.

Aside from appreciating the good stuff more, she says, it can produce art,

literature, poetry and spirituality.

‘They are often keenly spiritual people,’ she says. ‘Sometimes they are into the

wrong things, but they are very sensitive to spiritual things. If anyone spends

time looking deeply enough at themselves, you realize there is more below the

surface.’

‘They are very spiritual,’ agrees Marcus. ‘There is a big Romantic side to them.

They are fascinated by the supernatural and want to explore that.’

Contrary to popular belief, this does not translate to Goths being Satanists, he

adds, apart from a very few. ‘In fact, it is a very fertile ground for the

Church to reach out to.’

Marcus has conducted a Goth Eucharist in Cambridge every other Tuesday for

nearly two years, which regularly attracts 30-40 people.

The service itself will include Goth music, lots of candles, and sermons have

been on topics that have included self-harm, depression and suicide.

‘Rather than preach a kind of “All things bright and beautiful” message – cheer

up because Jesus loves you - I have tried to be honest and draw alongside

people,’ explains Marcus.

‘The service is not too patronizing, and it does not encourage people to wallow.

The last two songs are always more happy Goth songs, and the general message is

that there is light through the darkness.’

So it seems that Christianity and Gothicism are not incompatible. In fact some

argue that they complement each other quite well.

Joe easily reconciles the idea of seeing beauty where it would not immediately

be obvious with his Christian faith. ‘Jesus died on the cross, which was

incredibly horrific. But what came out of it was beautiful.’

Ash had been a Christian for a long time before she got into the Goth scene.

‘Over time, I found being a Goth didn’t replace being a Christian, but that

actually the two complemented each other,’ she says.

‘Christianity for me has always focused too much on happiness – the end when we

go to heaven – and skates over all the bad stuff. Goths are interested in the

difficult questions about the life we are facing now.’

I ask Ash if she’s happy. ‘Most of the time. The falseness of the world saddens

me, but I’m not sad. I think if I was purely a Goth I would be, but as a

Christian I know there is something bigger and greater than I am. He’s much more

gutted about the falseness than I am. He’s going to sort it out.’

Being a Christian and a Goth makes you a minority within a minority, which all

agree can be difficult.

‘The worst thing about it is the loneliness,’ Ash says. ‘Often in a church it is

just you. There’s a duality – you are very lonely as you are, but you can’t stop

being what you are. People say to me, “Why don’t you dress normally, then you’d

have a better chance of fitting in?” But when I dress normally I feel incredibly

awkward and uncomfortable. I feel like I’m not being real.’

This perhaps explains the growing number of Goth churches and alternative

services. It’s a place where you can be with people who share all of your

identity, not just a part of it. While the Goth Eucharist is conducted as part

of the normal Anglican church, Asylum is a church for people on the alternative

scene, which is independent and non-denominational.

They meet in The Intrepid Fox, an alternative pub in London, and try to ‘reach

all the subcultures’ through meetings which are broadly discussion-based, with a

focus on creative worship.

It started as a way of reaching out to non-Christians in the alternative scene,

and also for Christians who didn’t feel they belonged in the conventional church

setting, explains Billie Sylvain, the founder.

‘It’s been really good to meet others in the alternative scene who do love God

and for them to not feel as though they are the only one,’ she says.

Another reason for these churches is that Goths and others have suffered

rejection at the hands of the traditional Church for the way they look. ‘Lots of

people who are part of Asylum have these stories of rejection,’ says Billie. ‘I

have had people asking how I can be a Christian when I dress the way I do.’

So while their expression of Church couldn’t be more different, Billie and

Marcus’ motivation is very similar. ‘My service is full of people who, rightly

or wrongly, feel that they have been excluded from normal church. I just looked

at all these hurting people and thought “Surely this is where Jesus would be”,’

says Marcus.

‘It’s just sad the modern church is keeping within it’s boundaries,’ adds

Billie. ‘Jesus went specifically to the outcasts in society, in this day and

age, that doesn’t seem to happen.’

While Christian gathering specifically for alternative people are one answer,

neither thinks this is a reason for the ordinary church to turn their backs.

There is a universal call for the Church as a whole to be less condemnatory and

more inclusive.

In Ash’s view this is something that Goth’s often get right and Christians do

not. ‘It’s about inclusiveness. A Goth will sit down and talk to you, find out

where you’re coming from.’ She has had no problems with her non-Christian Goth

friends accepting her faith, but lots of problems from the church accepting the

way they look.

Marcus thinks it is essential that people get over the issue of what people look

like. ‘The big problem, and challenge, is to try not to be judgmental about the

way somebody dresses. You have to see what is good in them, not try to change

them, but make them realise that Jesus is alongside them. They’ll find God on

their own terms’.

Joe’s message is simple; ‘I’m not a creature from the black lagoon. We’re normal

people. Come and talk to us.’

So, Kimveer Gill was a Goth and he did shoot a lot of people. Some Goths are

Satanists. And they do wear a lot of black. But the ones I met were warm and

friendly, and their main complaint was of being misunderstood and excluded.

There’s an interest in spirituality – and a search for something deeper than

this world has to offer. A lot of them don’t feel that they belong here, but are

just passing through.

Perhaps Christians and Goths have more in common than either would ever imagine.

The Baptist Times, Thursday, September 21, 2006 -

by Ruth Dickinson